-

Conflict of interests: savers are missing out on rate rises, could CBDCs help?

The Financial Conduct Authority put UK banks on notice last week to pass on interest rate rises to their savers, or else be ready to suffer the consequences:

Firms offering the lowest savings rates will be required to justify by the end of August how those rates offer fair value, according to the Consumer Duty*

FCA 2023It’s a debate that’s playing out across the world, from Australia, to India, to America. Interest rates are rising, but savings rates are lagging behind. Banks are making money in the process with the rise in net interest margin (the difference between what banks pay on their liabilities – like deposits – and charge on their assets – like mortgages) one of the major drivers of increased profitability across the sector. UK banks are actually better than their global peers, according to S&P research, passing on a leading, but still less-than-stellar 43% of rises to consumers, while Ireland and Slovenia prop up the table with a paltry 7%. Politicians and regulators are responding, with Italian banks in for a nasty surprise yesterday with a 40% windfall tax on their profits, with their treatment of savings cited as one of the major reasons.

Pay me my money down

Why the needs for regulatory and political pressure? Shouldn’t market pressure alone cause banks to compete to offer the best rates? There are three reasons why this isn’t the case.

One is that the post-financial crisis regulatory regime has increased the barriers to entry for new entrants into the financial system. Additional capital requirements and heavier regulatory rulebooks serve the important purpose of protecting the economy from a repeat of 2008 and its aftermath, but at the cost of a more consolidated, less competitive banking sector.

A second is that banks are offering better rates, but only on term-deposit accounts that require customers to lock their money away for a defined period of time. In the UK, rates of just over six percent are available, but require a minimum term of a year. With the cost of living crisis biting, its easy to see why customers are reluctant to lose access to their funds in the meantime.

A third is the general ‘stickiness’ of deposits, with inertia driving many customers to the default savings accounts or current accounts that offer the lowest savings rates.

All this contrasts significantly with the money banks themselves hold with their central banks. In the UK alone, banks stand to make double-digit billions in interest from the Bank of England over the coming years, with their deposits held with the bank remunerated in full at the prevailing base-rate.

Livin’ in the future

As Andy Haldane notes in piece on the Financial Times last week, one of the CBDC topics that has not yet created much public debate is whether consumers ought to have the same benefit as banks from their money held with the central bank in the form of a CBDC: i.e., should your CBDC holdings be interest-bearing, just like banks’ are today. The general response of central banks to date has been an equivocal ‘no’, with the Bank of England hardening this view in their recent proposal for a digital pound stating that ‘no interest would be paid’.

This response is driven by a number of factors, namely that CBDC is meant to be a cash-like product, and like cash, it will continue to not pay interest; that CBDCs pose a threat to Commercial Banks’ business models, with interest payments exacerbate this threat; and that this effect could be particularly harmful during a time of crisis if consumers were to flee to the safety that CBDC offers as a direct liability of the central bank. I’d agree with Haldane that more debate is needed about this topic, which the arguments presented not necessarily aligning to a clear public-interest case, and mitigants such as daily limits on CBDC transfers seeming to have the potential to address many of the points raised.

In addition to his arguments, it’s also worth considering why central banks set interest rates in the first place. They do so as their main policy tool to try and influence the economy. Put crudely, when things are bad and they want to get the economy moving, they set rates low, like they did post-financial crisis. By making money ‘cheap’ to buy, they encourage more investment and spending. Conversely, during periods of inflation like we are currently experiencing, they raise rates, making new money more ‘expensive’ and deterring investment and spending in the present.

It stands to reason that a CBDC that paid interest at the bank rate would be a powerful lever of monetary policy transmission. Savers, from households through to businesses would have a reason to defer spending as they would know they would be getting the benefits of higher rates, helping to ease demand, and consequently, inflation.

Consumers and businesses are missing out on the rate rises that banks themselves are benefiting from, and that central banks want them to have as a tool of monetary policy transmission. We should think carefully about CBDC design and ensure that we don’t prematurely rule out what could be a an important public policy tool to both drive banking competition and benefit the public good.

*for the uninitiated the Consumer Duty is a new requirement on regulated institutions in the UK to “act to deliver good outcomes for retail customers”

-

Consider Not Feeding Your Eyeballs To The Orb

Image: Bing Image Creator

Interesting news yesterday as Worldcoin, the cryptocurrency company co-founded by Sam Altman of OpenAI fame, officially launched their services. They include a new cryptocurrency (the eponymous Worldcoin), an identity service, and an app that allows users to buy and sell cryptocurrencies.

Followers of the crypto space might have thought founders called Sam promising to re-invent finance’s moment had been and gone, but apparently not. Here we get the usual grandiose claims, but with the added sprinkling of AI:

Worldcoin could drastically increase economic opportunity, scale a reliable solution for distinguishing humans from AI online while preserving privacy, enable global democratic processes

Let’s take a look at the two key things they claim they’re doing.

Digital Identity:

Worldcoin claim to have created a unique ‘Proof Of Personhood’ (PoP) approach, centred on their custom-designed “Orb”. The Orb is a shiny silver device that captures pictures of your face, your temperature and your irises in order to prove that you are a unique, living human and then uses this fact to verify you onto their network as worthy of receiving your free grants of Worldcoin.Worldcoin make a big deal of privacy in the user-facing messaging, saying reassuringly that ‘images of you and your iris pattern are permanently deleted as soon as you sign up’ and that ‘the images are not connected to your Worldcoin tokens, transactions or World ID’.

However, if you dig into the documentation a little more you can see that all is not quite as it appears. If, like me, your mind instantly thought ‘but wait, how can they prove the next person is unique if they don’t keep a copy of the irises?’ Well, it turns out, that’s exactly what they do. They create what they call an ‘Iris Code’ – a series of ‘numbers’ that represent your irises.

This is just a sleight-of-hand to say that what they’ve actually done is turn their images into data. Those data represent the most meaningful and verifiable bits of the image: i.e. they represent your unique iris information. In the same way that a dental record can identify you without having actual images of your teeth for comparative purposes, so too can the Iris code. That information is stored against your account and your identify, which makes their claims to be ‘privacy preserving’ spurious at best, and outright misleading at worst.

Even with strong encryption this still poses a significant data-loss threat to personally identifiable, immutable information about Worldcoin’s users. This ranges from the near term – the classic threats of bad design, or bad actors getting hold of the data, to medium term, with nation states already harvesting data now to decrypt with future quantum computers later, to worries that Altman himself has expressed around the future of AI.

If, as OpenAI claim, we could have human level AI within the next decade, there’s every reason to believe that these data may not be secure forever. At the time of writing Worldcoin are offering around £40 worth of their token to those who have their Irises scanned. For me, it’s certainly not a risk worth taking. I’d be particularly interested in seeing the findings of the security audits that they bury in the further information section of their whitepaper that they have acknowledged but not fixed…

Increasing Economic Opportunity?

Let’s imagine for a moment that people get over the ‘ick factor’ of sharing they eyeballs with the Orb. What then? The basic premise of the ‘currency’ seems to be to give ‘grants’ to all users on an ongoing basis, simply for being human. This seems difficult to square with their product lead’s statements to the Financial Times that “All our products are for-profit. There will eventually be a bunch of different wallets and experiences which will make money.”

And yes, when you dig into the whitepaper you can see that 25% of all of the ‘coins’ they ever plan to release have been reserved for the creators of the network and their investors. Nice to know the utopian AI future will still have an upper-class of benevolent coin creators I guess.

Leave a comment

-

CBDCs: a powerful new tool for autocrats?

In 2011 I was lucky enough to travel to Beijing as a guest of the Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press. From the moment I set foot in the Foster and Partners designed international airport it was impossible not to be impressed with the scale of the place, a feeling that was only emphasised as our minibus traversed through the city’s rings, passing glittering skyscrapers and glowing billboards. I was there to act as an instructor and judge for the national English-language debating championships. One hundred and twenty-eight teams from one hundred and twenty-eight different universities took part, and it felt to me at the time that I was one small part of China’s slow opening-up to the world. Sitting out on plastic chairs in the humid summer evenings I had the chance to chat openly with our hosts as we ate duck cooked over an empty beer can and crispy chilli potatoes. Helping the students with their arguments, we had the chance to explore ideas together. The decade since has shown a Chinese state that has looked inward, closing itself off from the world. Xi Jinping has tightened his grip and now looks set to rule indefinitely, growing ever more authoritarian by the year.

Under no circumstances say there’s a similarity between these two

His appalling treatment of China’s Uyghur minority is well documented to the point that it’s easy to become inured to the savage barbarity of it all. Over a million people have been detained in ‘re-education’ internment camps. Women’s bodies are attacked with the forced use of intrauterine contraceptives, sterilisation and abortion in what has been termed a ‘demographic genocide’. Facial recognition cameras search for Uyghur ethnic features trained by datasets taken from coerced prisoners and curtail freedom of movement.

Ross Anderson, writing in the Atlantic in 2020, argued powerfully that far from being a localised issue, Xianging province is really a testing ground for technologies that are likely to be rolled out across China, and perhaps the wider world.

“In time, algorithms will be able to string together data points from a broad range of sources—travel records, friends and associates, reading habits, purchases—to predict political resistance before it happens. China’s government could soon achieve an unprecedented political stranglehold on more than 1 billion people.”

Indeed, just two years since he wrote the piece we have seen both the horrendous crack-downs on liberties in Hong Kong and the growing use of technology to control people’s lives. A month ago in Henan province individuals whose current accounts have been frozen were prevented from protesting. Their covid health passes suddenly flipped from green to red locking them out of public transport and public places on the planned day of the protest.

I’ve written about how Central Bank Digital Currencies have a lot of promise – to ensure a role for state money, and reduce cross-border transaction costs, to facilitate an ecosystem of money, but as with most technologies, there’s a concern over how it could have a ‘dual use’. CBDCs could present a powerful new tool in the management and oppression of citizens in authoritarian states. Financial data, combined with a digital identity, can draw connections between individuals and their network of associates with great clarity. Where and how people choose to spend their money reveals much about their preferences. A subscription to a liberal-leaning magazine, a payment to a friend tagged as a troublemaker, the wrong ethnic profile: all these data could be used to identify and supress dissent. CBDCs are coinciding with a decline in the use of cash, and in authoritarian states it is easy to imagine a diktat that all transactions – certainly in cities and other technologically advanced areas where citizens would be expected to have access to digital technologies – must take place in CBDC, creating very little space to hide. Even an absence of activity may itself become to be considered suspicious as it has for Uyghurs who stop using their mobile phones.

Commercial banks used to pride themselves on being secret-keepers for their customers. Over the years, regulators have ensured they know who those customers are, and are monitoring for suspicious activity and reporting it to the authorities. However, the current system is still containerised with individual banks holding data about customers separately to each other, and no single state ID or ‘single file’ existing for each citizen. China’s banking and payments system has super apps at its heart like Ant Financial. It’s charismatic founder, Jack Ma, thought he was powerful and connected enough to level some relatively light criticism at China’s banking system. He was summoned to meet regulators, their IPO was cancelled wiping $76bn off the companies value and he disappeared from public view for three months. The private sector operates at the discretion of the party, and the leash is short. China have shown moves towards creating singular state records of citizens tying multiple data points together. Their moves towards CBDC, combined with their crackdown on their own tech sector shows how feasible it is that they could use these financial data to further oppress their citizens.

The programmable and centralised nature of CBDCs could be directly brought to bear to circumscribe citizen’s freedoms, both actively and through financial nudges. Posting the wrong thing on social media, joining a protect, or leaving a designated geographic area could feasibly result in an individual being frozen out of their money or placed on the monetary equivalent of emergency rations. Pro-regime behaviours and spending could be subsidised and rewarded using the programmable features of CBDC to incentivise spending with party-affiliated activities and loyalty. This may sound Orwellian or like a China scare story, and some of their early CBDC developments do make provisions for some level of privacy, but as both the morphing use of their covid apps and the wider treatment of their own citizens shows, it’s a frighteningly real possibility the once adoption becomes widespread it could be used as another tool of control.

Tied into this concern is how China has become a major exporter of oppressive technologies to other authoritarian or would-be authoritarian regimes. Several of these countries have shown early signs of wanting to create interoperability between their putative CBDCs. While this could come with the benefits of eased cross-border payments, it could also portend a more atomised global financial system, with less reliance on traditional western intermediaries such as Swift and the IMFs special drawing rights and a move towards an authoritarian money axis. Recent sanctions against Russia show both the strength and the limitations of the west’s ability to use financial architecture as a lever: a new infrastructure that bypasses the control or oversight of western states would make it much easier for authoritarian states to operate around sanctions and restrictions in their dealings with each other.

I sometimes think about the students and lecturers that I met in China – about their arguments in the debates I judged about the need for the state to reflect the wishes of its citizens in order to maintain its legitimacy, about their hopes for themselves and their country– and wonder how they are doing now. I hope for their sakes that my fears about how CBDCs could be appropriated as a tool of control are misplaced.

Leave a comment

-

How might CBDCs impact cross-border payments?

“What’s a scam that’s become so normalised that we don’t even realise it’s a scam anymore?”. So starts a viral TikTok that goes on to highlight the ever increasing costs of student debt. Other users have taken the prompt to stitch their own videos and provide their examples of what they think are scams. Hospital bills, funeral homes, the fashion industry, wellness, and society’s relationship with alcohol all feature. One that doesn’t, perhaps because it’s so insidiously entrenched that peopled don’t even think about it, is the cost of sending money to a loved one abroad. One in nine people around the world are supported by funds sent to them by migrant workers. Half that money goes to rural communities where the word’s poorest people live. These payments, called remittances, are a vital lifeline for many. They are also the reason so many workers make the hard choice to leave their families and communities behind to forge a new life in new surroundings. And yet they remain extortionately expensive. Each transaction of this hard earned, desperately needed money attracts fees in the region of seven percent, or over ten percent to large parts of sub-Saharan Africa. How did we get here when we can send an amusing video of a cat containing thousands of times more data than the payment instruction for effectively nothing, and yet the tiny amount of text based information required to send a payment extracts such a large rent?

The answer, frustratingly, is not a simple one. One, for sure, is the profit that money transfer businesses extract from their customers. They get you every which way. A fee to send the money. A hidden fee by providing you with a rubbish forex rate. Want to actually use the money? There’s a withdrawal fee for that. Got more than you were expecting? There’s a fee for being over your expected account limit. ‘Purpose driven’ Western Union, who returned more than $700m to shareholders from revenue of just over $5bn in 2021 and charge an average of “around 5%” per transaction lay out the risk in their annual report. They worry that regulation could “adversely affect their financial results” as “price reductions generally reduce margins and adversely affect financial results in the short term and may also adversely affect financial results in the long term if transaction volumes do not increase sufficiently” [sic]. Conspicuously absent from their environmental and sustainable governance report is any mention of the UN’s 10th sustainable development goal which aims to reduce the average remittance cost to below 3%.

Global finance’s approach to remittances However, simply picking on the transfer agents is unfair. There are costs through the whole system. The agents use a network of banks who each take their cut. Regulatory requirements differ by country but include the need to ensure the sender and receiver are known and not on terrorist watch lists adds an extra burden. The infrastructure underpinning it all was cutting edge at some point in the 60s but adds cumbersome costs now. Operating across different time zones presents its own challenges.

Live view from inside AN Other Bank’s core banking system

Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) present a rare opportunity to address this problem, and policy makers have taken note. The ECB recently released a paper on the ‘holy grail’ of cross-border payments, and The Bank of International Settlements have also highlighting the opportunity. The ECB define that holy grail as payments that are “immediate, cheap, universal, and settled in a secure settlement medium”. A secure settlement medium essentially meaning that the currency isn’t subject to huge fluctuations or instant collapse like the unfortunate holders of certain so-called stablecoins recently. They argue this is within reach in the next decade. Interestingly, the ECB also notes, positively, that CBDCs – as opposed to Meta’s Libra which we explored in a previous post – expressly ‘preserves the dominant power of existing issuers’ – i.e. preserves the powers of the governments that issue legal currencies today and prevents the private sector from stepping on their turf.

There are several reasons that CBDCs present this opportunity, but three in particular stand out:

- Because they can run on new hardware and software, they can leave behind the legacy complexity that gums up the existing system

- As they don’t yet exist, they can be designed cooperatively by central banks from the ground up to interlink, for example through the agreement of common data standards, security architecture and other similar features. Early experiments in this regard have already been conducted by some central banks.

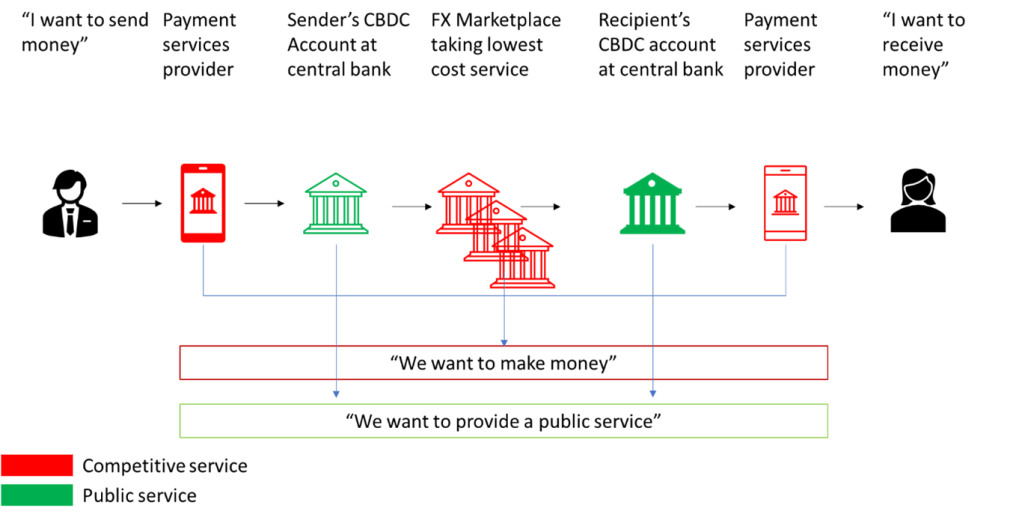

- Central banks can design CBDCs in a way that allows for competition facing the user i.e. multiple payment service providers competing to be the front-end onto your CBDC account at the central bank – perhaps even with a mandated ‘free tier’. Similarly, central banks can mandate competition and in the middle by allowing a marketplace of FX providers each competing to provide you with the lowest cost option.

Illustrative example of how a competitive cross-border CBDC ecosystem might reduce costs

Of course these benefits do not just accrue to remittances. While they are some of the most egregious examples of under-served customers, everyone, from businesses through to citizens could benefit from the ability to more cheaply, easily and rapidly use foreign currencies. For the poor, CBDCs are not a panacea. They come with their own risks and downsides, and many customers will still be digitally excluded as they can’t afford a mobile phone or lack a state ID necessary to register with a payment provider. However, the current system operates to enrich the rich at the expense of the poor. Anything we can do to try and address that most obvious of scams is surely worth considering.

BRIEFLY NOTED

- Use of cash may be increasing again as people use it to help manage their spending in the face of rampant inflation

- Everyone’s favourite drug-pushers on whether banks should look to modernise their core banking infrastructure

- The vampire squid attempt to frame the future of Web 3.0

- BIS on CBDCs and financial inclusion

Leave a comment

-

Why are central banks considering introducing CBDCs?

IN 2010, a commenter on the blog of rationalist community Less Wrong going by the name of Roko sat down at his keyboard and got ready to inject a cognitive virus into the minds of his readers. For years Less Wrong had been a place for intelligent geeks and oddballs interested in the future of humanity to hang out and share their thoughts on everything from where tech was going to how humans make decisions. Some of those users were believers in the so-called singularity: the idea that, as computational resources continue to double, and our software development capabilities advance, we will reach a point some time this century where we create a true artificial intelligence, as smart as the smartest human.

The thinking goes that as soon as that point is reached, this machine intelligence, with the ability to spread its wings across the computers of the globe would make billions of copies of itself, undergoing a sort of Cambrian explosion of intelligence as it upgrades and augments itself, consuming all the existing knowledge and data of humanity as it goes, almost instantly becoming a god-like ghost in the machine. The fervent hope of the utopians in the Less Wrong community was that this moment of singularity, named after the heart of black holes where the rules of the universe cease to act as a constraint, would lift us up out of the misery of our human condition; of war, strife, disease, pestilence, and scarcity and instead lead us to the green pastures of the promised land. That the machine would care for us, or we would fuse with godhead of the machine, or both. That, like a parent who has become enfeebled, the computational child of humanity would turn to us and smile wanly and tuck us up snugly under a warm blanket. Roko wasn’t so sure.

Elon Musk and Grimes Apparently went on their first date after a Roko’s basilisk joke on Twitter

The theory he set out that July morning went something like this: imagine that in the future, there is a superintelligence. Further, imagine that this superintelligence really likes existing. Now imagine that, as a consequence, they decide to reward everyone who caused them to come into existence, and punish everyone who didn’t, torturing them in the virtual hellfires of Iain M Banks’ Surface Detail. This superintelligence has computational abilities that are so far beyond our imagining that they are god-like. They can read your thoughts or simulate hundreds of copies of you that are identical to you, just simulated inside a machine. They could even simulate you in a perfect copy of the past to determine whether you would have helped bring them into existence or not. In fact, that simulation would be so indistinguishable from reality that you could be in it right now. With only one base level reality, but billions of possible simulations, you’d have to imagine the odds are that you are in a simulation and not reality right now. If that’s the case, then the AI that punishes you for not causing it to come into existence already exists and is likely testing you for treats or torture right now. In that world, surely you ought to at least try and cause it to come into existence; after all, you are not causing the harm of tortured souls because the odds are you are already in the simulation, so the harm already exists. And if you don’t help it come into existence it might send your digital soul to a digital hell for all eternity. While real hell might not exist, one created and controlled by a supreme artificial intelligence would basically be indistinguishable.

With a delectable menu of tortures available you’d better be kind to the basilisk

You can imagine the impact this line of thinking had on the techno utopians, who had, to that point, imagined a future where they symbiotically merged with the machine to control the laws of physics and gravity and explore the wonders of the universe. Here was their god, but dirty and corrupted and altogether too human in its nature. Eliezer Yudkowsky, the founder of the community did not hold back, replying at just after five in the morning

Listen to me very closely, you idiot

YOU DO NOT THINK IN SUFFICIENT DETAIL ABOUT SUPERINTELLIGENCES CONSIDERING WHETHER OR NOT TO BLACKMAIL YOU. THAT IS THE ONLY POSSIBLE THING WHICH GIVES THEM A MOTIVE TO FOLLOW THROUGH ON THE BLACKMAIL.

You can almost hear him screaming to himself as the dawn light starts to curl around the edges of his bedroom curtains and he contemplates the day ahead. “FUCK, now that’s in my mind, I have to go and make a fucking evil AI just to not be tortured forever. Thanks a fucking LOAD Roko”. To a certain type of person like Eliezer, a frightening idea had been born that came to be known as Roko’s Basilisk, like its mythical serpent king namesake; if it can see you, it can kill you. If the idea of it exists, then inevitably it will come to exist.

Last week we asked ‘what are CBDCs’, and we explored some of the reasons that central banks might introduce one, including

- Wanting to maintain citizens’ access to state money – that is, money that is directly issued by the state, and, unlike bank deposits, doesn’t require citizens to take on credit risk to commercial banks

- Facilitating the development of new ecosystems around money by enabling new features, such as ‘programmability’ that allows the automated execution of payments

- Near real time settlement finality – that is, money doesn’t spend hours or even days passing between a network of banks before you know the recipient has it: it gets there right away

- Worries about the quality and stability of private payment networks

- The desire to preserve financial inclusion and ensure that everyone can access the financial system as the use of cash decreases

- A desire to lower the cost of cross-border transactions that currently saddle some of the world’s poorest citizens with unconscionable fees

- The unstated desire to be able to exercise a greater level of control over citizen’s financial activities, particularly in authoritarian countries. As the world has learned the hard way in recent years, even in liberal democracies, where the capability exists for nefarious leaders to act nefariously there’s every chance they might

But these reasons aside, I’d argue that there is a baser motive at play: fear. Like the netizens of the Less Wrong forum, central bankers have heard the idea struck like a bell in the darkness, and now they can’t unhear it. For example, if you read the initial consultation paper by the European Central Bank, you can see a similar line of thinking in operation. The paper talks about what the requirements for a digital Euro might look like, but makes clear that part of the reason that the ECB is looking at the topic at all is that if they don’t, events might overtake them. In the words of Fabio Panetta, one of their executive board members, they must issue a Digital Euro “if and when developments around us make it necessary. This means that we already need to be preparing for it.” (my emphasis)

Nobody wants to be stuck in the chamber of secrets without a sorting hat

If the promise of CBDCs to consumers and businesses turns out to be real, then whoever introduces one first will have huge advantages. Nobody wants to be stuck in the chamber of secrets without a sorting hat while Tom Riddle saunters off with your galleons. Imagine a world where corporates can hold risk free money in another country’s currency: the odds are when we hit the next crisis you will see money cascading across the border. At that point, with so much of your citizen’s and companies’ money held abroad it would become incredibly difficult for the central bank to influence the economy with monetary policy. If a good portion of your country’s money is not held in your currency, then it matters a lot less at what level you set interest rates because the currency your citizens are using day to day isn’t affected by them. This process is called currency substitution.

Similarly, imagine if an ecosystem around money does develop with CBDCs. The programmable money features many central banks are considering may result in a huge number of providers coalescing around one currency. Data providers, solicitors, and citizens all using the most feature rich money, akin to Apple and Android’s dominance of the mobile world. While the crypto world’s unregulated nature has burned many citizens, its shown a tantalising glimpse into the potential for more digitally enabled money, finance and assets that we’ll explore further in coming weeks. For now, suffice to say many central bankers worry that they’ll be left all alone while the party has moved on to a house they aren’t invited to.

Is anyone out there building a basilisk? Do we live in her simulated world? Is it a purely conceptual concern that catches the imagination of a small community but fails to spread wider? Only time will tell…

Briefly noted:

- A great article examining the ‘unprecedented privacy risks of the metaverse’. “Thirty study participants playtested an innocent-looking “escape room” game in virtual reality (VR). Behind the scenes, an adversarial program had accurately inferred over 25 personal data attributes, from anthropometrics like height and wingspan to demographics like age and gender, within just a few minutes of gameplay.”

- Differential cash preferences across age groups: the older you are the more you want to use cash, and a lot of people still prefer to give cash to friends and family

- The Financial Action Task force discuss the principles for sharing data cross-borders to fight financial crime

- The IMF publish John Kiff’s piece examining offline payments for CBDCs

- Ori Frieman discusses some of the political implications of introducing a CBDC

Leave a comment

-

What is money anyway?

This post is the first in a series called ‘central bank digital currencies 101: what are they and why should I care?’. This first post explores the different kinds of money in the economy today

Let’s start this week with a personal question: how much money do you have? It might sound like a simple question, but it is surprisingly difficult to answer. When you answered, did your mind immediately go to the balance in your bank account? How about the money in your purse or the proverbial – or real, no judgement here – cash under your mattress? While you might think of money in your pocket and money in the bank as the same thing, they are not. In the economy at the moment there are really three different types of money, and they all have different qualities and features.

Cash

The first type of money is cash. Think about the money in your pocket again. If you haven’t already abandoned cash entirely, take it out and look at it. What do you see? On the front of the British ten pound note in front of me I’m met firstly by the face of our hereditary monarch, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth The Second, Defender of the Faith and Seigneur of the Swans (seriously) and her fetching ‘ERII’ logo. The words ‘Bank of England’ appear seven time across the front. A portcullised arch and the royal crown are embedded in the security holograms, and the emblems of the four nations of Great Britain and Northern Ireland sit squarely in the middle of the note.

You don’t have to be a Dan Brown style symbologist to take in the fact that this is an instrument of the state. It practically screams it at you. On the reverse of the note the fetching portrait of Jane Austen looks like a pastoral scene, but look closer and what looks like etching marks on an engraving behind her is actually the letters ‘BOE’ repeating again and again so many times that I gave up the will to count them all. Far from being a uniquely British phenomenon, the same is true of government bank notes around the world: cash is explicitly, overtly, smack you over the head obviously an instrument of the state.

Cash is also unusual in that it is highly private. Cash comes without memory, and cash is available to everyone. For this reason it is favoured by the tax averse, the privacy conscious, those avoiding transaction fees, and those who struggle to gain access to the banking system. (We’ll explore these features in a later post.)

Bank Deposits

The second type of money is bank deposits. Now that you’ve taken a look at a bank note, open up your online bank account on your phone or your computer. Before you click into it, have a look at the icon they’ve used. What about the name they have given it? Now click inside, what logos and colours greet you? The difference is obvious and stark: while the world of the bank note is the world of the state, the world of your bank account is the world of that bank. The only visual similarity between the two is likely to be the symbol used to denote the currency in your jurisdiction. This is not just a branding difference, but is actually an insight into the differing natures of bank notes and bank deposits.

Cash, as in notes and coins, are state issued money you hold without any intermediary. That is to say you don’t need a bank, or a PayPal or a Facebook, or a Mastercard in order to have, and use, cash (although it is in all of their interests to cajole you into using them as much as they can so they can take their cut of your money). A bank deposit on the other hand is, if viewed from the bank’s perspective, money that you have chosen to lend to the bank and as such sits on their balance sheet as a liability, not an asset.

Most people are familiar with the idea of credit from a credit card; credit is a loan extended by one party to another party. While many people don’t think about it, when you deposit money into a bank account, you are taking on credit risk to the bank. Put simply, if the bank goes bust, you might not get all your money back. That’s because the bank does not put ‘your’ money into a particular vault and keep it safe for you, adding a few pennies of interest every month to your little hoard with all the bitterness of a Gringotts goblin. Instead they use your money; to help them lend money to your neighbour to buy a house, to pay their staff, to hedge their exposures.

Generally we accept that this poses us a minimal risk, and most states operate some kind of deposit guarantee scheme to protect small deposit holders, but the risk exists none the less. The Bank of Cyprus depositors who lost 47.5% of their savings in 2013 in what was described at the time as a ‘haircut’, but probably felt to them more like a trepanning, can attest to the fact that bank deposits are not as safe as they appear to be. This is important because, as the use, acceptance and availability of cash decreases, so does your ability to hold risk-free state money. If all your money exists only as a number in a bank’s computer, your financial fate is totally tied to the behaviour of that bank.

Central Bank Reserves

Turns out there are no funny images about central banks. Let’s work on that Banks themselves have access to a third, special, kind of money, namely central bank reserves. This money is electronic state money that a small number of licensed operators hold in a special account with the central bank in their jurisdiction, so Deutsche Bank with the Deutsche Bundesbank, JP Morgan with the Federal Reserve, Barclays with the Bank of England and so on. The central bank creates this money out of nothing – the economy is like a game of Monopoly: if the bank starts without any money then nobody can play the game. The commercial banks swap other assets – like bonds – for this money which is then credited to their accounts. They use the reserves to settle up the balances that result from all of our individual daily transactions, so if I bank with Nationwide in the UK and send £100 to my friend who banks with Barclays, my transaction appears at the central bank as Nationwide and Barclay’s ‘settle’ the aggregate movement of money between them.

Holding an account with the central bank comes with conditions like needing to leave a certain amount of money in the account at any given time to make sure you can pay all your bills. It also gives the central bank insights into the flow of money between the banks, which has become increasingly important to them as many have taken on regulatory and oversight responsibilities for their domestic banking sector. The amount of reserves held by banks has swelled massively since the global financial crisis due to quantitative easing. It’s about to net them a very tasty profit (reportedly upwards of £57bn in the UK) as the bank pays them interest on all that new money.

Central bank digital currencies

The idea behind a central bank digital currency is an alluringly simple one: to create a fourth type of money that takes some of the features of the types we already have. Tune in next week to find out more!

—–

Postscript:

This is only post two of the blog, and the first of the kind of content I imagine I’ll be posting most weeks, so I’m keen to get your feedback! Enjoyed it? Let me know. Think someone else would enjoy it? Share it with them. Have questions, comments or observations or want to join the conversation – please dive right into the comments.

Further reading:

- If you’re looking for a more technical overview, this Philadelphia Federal Reserve working paper is a good place to start.

- The bank of England provide some helpful overview of how reserves function, and an overview of cash in the time of Covid with some interesting insights.

Briefly noted:

- Minecraft have banned NFTs as they create exclusivity and are against their values

- Financial regulators are looking seriously are regulating big tech across their entire group structures in order to manage the risk they pose in the financial sector (predict this could become a big story)

- The SEC have classified digital assets as ‘securities’ and charged a Coinbase staff member with insider trading

- Irish village sports team loves cash and is angry at their bank for taking it away

4 responses to “What is money anyway?”

-

I’ve spent a bit of time thinking about the conflict between bank deposits as 1) a safe store of value and 2) a low risk investment.

Banks have an incentive to not get you thinking too much about the paltry amount of interest they’ll pay for your money. ‘Free in credit’ banking also fuzzes the lines too.

It feels like a big step to move out of savings into investments, but I wonder if that wouldn’t feel as jarring if we better appreciated the price we pay for the ‘safe store’ bit, and so had an incentive to distribute our money further up the risk tiers

LikeLike

-

[…] This post is the first in a series called ‘central bank digital currencies 101: what are they and why should I care?’. This first post explores the different kinds of money in the economy today—Read more […]

LikeLike

Leave a comment

-

Let’s get started, shall we?

A year and a half ago I had a surreal experience of meeting the Editor of the Financial Times, Roula Khalaf, and McKinsey’s soon to be ousted managing partner, Kevin Sneader, in my living room. They chatted about a mutual connection in an easy manner that showed it’s a small world if you’ve been to Davos while the rest of us waited around a little awkwardly.

Six months earlier in the balmy sunshine of the Covid summer of 2020 I’d had ten days of quarantine to kill. Along with my government approved exercise regime I spent some time writing about a topic that had caught my attention: Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs). I’d known for a few years about the Bracken Bower Prize, a joint prize offered by The FT & McKinsey to the best new business book proposal by someone under the age of 35 and decided ‘what the hell, I’m not going to win but it at least gives me something to do with all the free time’. I dived into it, reading papers, playing with words, feeling a bit of life come back at the prospect of seeing friends and family after the wearying months of social distancing. I enjoyed the process. I loved leaving the route the sat nav suggested and exploring the side roads. I learned about how one of the Queen’s titles is Seignior of Swans and how the medieval guilds of London still count them on the Thames for her every year. I sent off my piece with the vague hope of making the long list but happy to have got a few words down.

Back with the esteemed company in my living room. It was the evening of the Financial Times’ business book of the year awards. Instead of the usual swanky ceremony in London or New York I was sat down at our dining table, wearing the slightly shaggy absence of a haircut that revealed the fact I hadn’t managed to get it sorted before Boris u-turned on restrictions yet again and Kent became a global swear-word and not our neighbouring county. My window on the world was a thirteen inch screen, their view of mine carefully framed to include the Ikea bookshelves my father in law had fitted so perfectly they look every bit an artisan’s instillation. On the shelves were a few books carefully placed in view because – well – you never know who is looking and you want to put your best book forward: Nick Harkaway’s Gnomon and Jill Lepore’s If Then, up for the main prize of business book of the year, if you’re curious.

To my surprise I’d made not just the longlist, but the shortlist. As the online ceremony ticked by with glitzy videos and a fireside chat (a sort of interview that other people listen to, without a fire as best as I can tell) it came to our turn. My heart beat faster in my chest. And then there it was, my name. I’d won. I was more than a little shocked. My incredible wife, Anna, sat just out of shot was beaming and clapping silently. Not quite sure what to say I asked the McKinsey partner if he wanted me to give a short overview of the piece. And then that was that. The window on the world closed and we were back to our living room. Anna grabbed a bottle of Furleigh Estate from the fridge. A few celebratory phone calls with family. Then the next day, the dawning realisation hit. ‘Fuck me, does this mean I have to write a book?’. The short answer was no. The prize was for a proposal, not a book, and it didn’t come with a contract or an obligation. But the long one was what an opportunity. Here’s something I love – writing, thinking, speaking with people – and a chance to do it properly with a bit of profile behind it.

I never expected to have a full page in the FT! Except life doesn’t always work out like that. I’d drunk nearly all the bubbly by myself because Anna was six months pregnant. On that same trip home where I started writing I’d brought photos for my parents from our first scan. It wasn’t our first pregnancy. But it would be the first where we got to bring our baby home, after the stillbirth of our daughter, Clara, in 2018. Blessedly, amidst a lot of stress and anxiety our son Alex was born healthy, if a little early to be on the safe side, in February 2020. I’ve never quite known what Joyce meant when he said “snow falls equally on the living and the dead”, but as the gentle snow fell outside the window of the hospital room and I held Alex in my arms for the first time it was that line that came back to me all the same. Ever since it’s been a blitz of parenting clichés of sleepless nights, giggles, exhaustion and jaw-dropping wonder at how this tiny bundle has turned so quickly from a helpless mite to the toddler standing beside me demanding to be fed dates.

Alex a couple of weeks after making his big debut And so the plans to write got placed carefully on the bookshelves along with the books I no longer have time to read. But that wasn’t quite it on its own. It was also the feeling of letting myself down slightly in not pursuing the big project of the book. Unfortunately I think I’ve let that feeling dissuade me from writing much at all. As if the two choices were write the book or write nothing. And so here we are 18 months later and I’ve decided that’s not the smartest way to think. I enjoy writing – love it even – and sure, why not do what I can? So I’ve decided to start this blog and to write something every week. It might not be the book. Not right away at least. But it will be fun and it might even be worth reading. It will mainly be about CBDCs and Finance but written in a way that I hope can bring more people into the debate without talking down to you. There might be the odd digression along the way. The scenic route is lovely after all. And if you fancy reading along and joining a conversation, even better.

Ever wondered what money is? We’ll start there next week.

4 responses to “Let’s get started, shall we?”

-

Really enjoyed reading this Stephen and I have a 200 word attention span so bravo!

looking forward to what’s to come.

LikeLike

-

Thank you so much, Clare!

LikeLike

-

-

Love this Stephen … looking forward to next week 😀

LikeLike

-

Thanks Alex, glad you enjoyed it!

LikeLike

-

Leave a comment

-

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

Leave a comment