This post is the second in a series called ‘central bank digital currencies 101’. To start with the first post that asks ‘what is money?’ click here.

Facebook wants our money. On the 18th June 2019, they launched a digital currency called Libra that aimed to do nothing less than “reinvent money and transform the global economy”.

With 2.7 billion people already using one of their apps across its Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp brands, financial analysts believed they could realise up to $19bn additional annual revenue.

What took insiders by surprise when the announcement came was that, while spearheaded by Facebook, it was from the newly minted Libra Association, a consortium of 28 organisations including major brands like Visa, PayPal, Uber and Spotify.

Hidden behind the technocratic language of an “efficient medium of exchange for billions of people around the world” that would “grow into a global financial infrastructure” was a promise, or, depending on your point of view, a threat: what we have done for social media, music, telecoms, and taxis we are going to do to money.

The difference from those industries that had already been ‘disrupted’? This time they were going after the state, and the state was not going to throw open the doors to its vaults without a fight.

The official response was abrupt, and coming from the reserved and academic halls of central banks and abacus-obsessed finance ministries, unusually forthright.

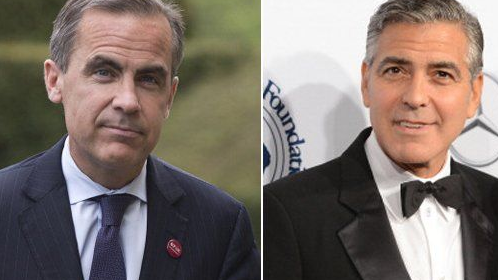

The Bank of England’s globally respected Canadian Central Banker Mark Carney (dubbed the “George Clooney” of finance by his fellow central bankers – they don’t get out much) described it as having a “very wide range of issues” to resolve.

France’s Finance Minister, Bruno Le Maire, put it most starkly when he said “the monetary sovereignty of the state is in jeopardy”. Digital currency had hit the mainstream, and the state was mounting a fightback. At the heart of that fightback was central bank digital currencies.

The idea behind a central bank digital currency (CBDC) is an alluringly simple one: to create a new type of money*. Specifically, electronic money that held directly by individuals or businesses with the central bank.

While intuitively this may feel similar to a commercial bank deposit does at the moment, this seemingly simple change has the potential to radically reshape the economy.

If individuals and businesses can hold money directly with the central bank, there will instantly be a system with the advantages of state money, like cash, and the advantages of the easy transactability, like bank deposits.

Better still, it would come without their downsides. You would no longer need to physically carry around cash or pile up coins gathering dust in an old jar when you spent a portion of your money. It couldn’t go missing in an untraceable way like cash can, and seems to do regularly, with the Bank of England saying recently that there is £50bn of cash unaccounted for.

And you’d no longer be carrying the risk of lending money to a bank, like you do when you deposit money into a bank account. Instead you would hold your money directly with the central bank – with the state – and while the state could go bust, the risk of them doing so is significantly less than the risk of an individual bank doing so.

With cash’s use and acceptance declining in many western countries, people who rely on it, such as the elderly or those with limited incomes risk being excluded from the financial system. A digital state currency could address this emerging harm and ensure financial inclusion for all across society.

By gathering all of the money in the economy in one place it could create a positive ecosystem effect where multiple providers are all investing in products and propositions to help you manage your money better.

With the right controls and incentives this could allow everything from ‘smart contracts’ that execute themselves (like your electricity meter reading itself and paying your bill for you) through to apps that help manage your money better, to academic insights that can allow us to manage the economy better by spotting trends or predicting GDP ahead of time in the massive dataset of all of the economy’s transactions.

With so many advantages it is easy to see people abandoning commercial banks in droves unless the central bank limits the amount you can hold with them

But risks abound. Now the state would have a single log or ledger of every transaction that you, and everyone else in the economy had made. As a recent Financial Times editorial stated “centralised ledgers would contain frightening amounts of information about their citizens’ behaviour”.

How would you feel about the state being able to check into everything you had ever bought, potentially even combining it with other data they hold about you? Check that you had paid your taxes and weren’t skimping on VAT? Had paid a subscription to Pornhub premium last month? Had paid £30 at regular increments along with dozens of other people to someone who seemingly didn’t have a job with a little herb emoji in the payment details?

You might delight in no longer giving money to your bank for a paltry return. What if you came to try and buy a house as a first-time buyer, but the bank no longer had any deposits? Perhaps the mortgage would be more expensive now because they no longer have the cheap financing of our deposits. Perhaps they would be unable to finance it at all so you would be unable to get a mortgage.

This is not just an academic concern. Central bank digital currencies are about to hit the mainstream. China is already in the process of rolling out a digital version of its currency. Concerned by the rise of peer-to-peer payments in WeChat and other super-apps, along with other non-state payment channels it is piloting its digital Renminbi currency with a population of some 400 million users across major urban centres.

Combined with their nascent attempts to create a social credit score, these are frightening implications of centralising money and removing cash from the system. Say something unpopular or uncouth online? Perhaps all your money will be frozen for a week. An automated CCTV camera algorithm identifies the Uighur ethnic features present in the person you are having coffee with, combines it with your financial data with and realises you have sent them money? Perhaps some re-education time to remind you of your civic duties is in order for both of you.

The state fightback against Libra worked. Cowed by the fierce criticism, many of the early backers started to run from the nascent currency and eventually it was quietly dropped, with its software stripped and sold to the highest bidder.

But the fear it sparked was real, and the response is still filtering through the system, and is likely to have a profound and long-lasting catalytic effect.

The worry stemmed from how realistic it was that consumers, fed up with traditional banks, unenamoured with the state, and often less concerned with privacy than policy makers are, might have chosen to abandon state currencies in droves.

To keep the state’s monopoly on money intact, plans for digital currencies have accelerated and are the talk of the global financial system.

Not since we moved away from the gold standard to fiat money has there been such a radical moment for our financial system. Over the coming weeks we’ll explore the implications and the choices we all face.

Briefly noted:

- Speaking of Facebook… Meta’s revenue declines while they look to double content from people you don’t follow in your feed, despite a user backlash

- “While the technologies for such currencies would be new, the use of the central bank balance sheet to provide state-backed transactional money is one of our most longstanding functions” – speech by the BoE’s Executive Director for Markets

- UK financial services regulations look to safeguard access to cash for ‘generations to come’, require regulators to ‘have regard’ to government policy, and introduces new secondary objectives for regulators including an aim towards net zero emissions

- Fascinating report from the Bank of Israel on financial inclusion, including that “that more than 50 percent of Arab respondents prefer… cash over other means of payment.”

- The World Bank explore the environmental implications of CBDC

- Barclays are running a two-day CBDC focussed hackathon in September

- If you want to dig into the history of Libra, the FT’s Alphaville ran an amazing series that looked at “how nonsensical, pointless, stupid, risky, badly thought-out and blockchainless the whole thing [was]”

*Central Banks the world over are considering the design of CBDCs at the time of writing. There are multiple choices that would need to be made, such as whether to allow customers to hold money directly with the central bank, or require them to go through a third party such as a bank or a payments provider. Rather than bog down these early explanatory posts in design decisions I’ve taken a maximalist view of what a CBDC may look like in a broad expression and we’ll explore some of the design choices in later weeks.

Leave a comment