In 2011 I was lucky enough to travel to Beijing as a guest of the Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press. From the moment I set foot in the Foster and Partners designed international airport it was impossible not to be impressed with the scale of the place, a feeling that was only emphasised as our minibus traversed through the city’s rings, passing glittering skyscrapers and glowing billboards. I was there to act as an instructor and judge for the national English-language debating championships. One hundred and twenty-eight teams from one hundred and twenty-eight different universities took part, and it felt to me at the time that I was one small part of China’s slow opening-up to the world. Sitting out on plastic chairs in the humid summer evenings I had the chance to chat openly with our hosts as we ate duck cooked over an empty beer can and crispy chilli potatoes. Helping the students with their arguments, we had the chance to explore ideas together. The decade since has shown a Chinese state that has looked inward, closing itself off from the world. Xi Jinping has tightened his grip and now looks set to rule indefinitely, growing ever more authoritarian by the year.

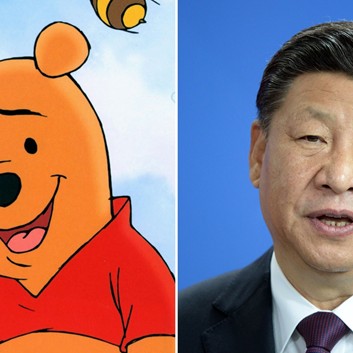

Under no circumstances say there’s a similarity between these two

His appalling treatment of China’s Uyghur minority is well documented to the point that it’s easy to become inured to the savage barbarity of it all. Over a million people have been detained in ‘re-education’ internment camps. Women’s bodies are attacked with the forced use of intrauterine contraceptives, sterilisation and abortion in what has been termed a ‘demographic genocide’. Facial recognition cameras search for Uyghur ethnic features trained by datasets taken from coerced prisoners and curtail freedom of movement.

Ross Anderson, writing in the Atlantic in 2020, argued powerfully that far from being a localised issue, Xianging province is really a testing ground for technologies that are likely to be rolled out across China, and perhaps the wider world.

“In time, algorithms will be able to string together data points from a broad range of sources—travel records, friends and associates, reading habits, purchases—to predict political resistance before it happens. China’s government could soon achieve an unprecedented political stranglehold on more than 1 billion people.”

Indeed, just two years since he wrote the piece we have seen both the horrendous crack-downs on liberties in Hong Kong and the growing use of technology to control people’s lives. A month ago in Henan province individuals whose current accounts have been frozen were prevented from protesting. Their covid health passes suddenly flipped from green to red locking them out of public transport and public places on the planned day of the protest.

I’ve written about how Central Bank Digital Currencies have a lot of promise – to ensure a role for state money, and reduce cross-border transaction costs, to facilitate an ecosystem of money, but as with most technologies, there’s a concern over how it could have a ‘dual use’. CBDCs could present a powerful new tool in the management and oppression of citizens in authoritarian states. Financial data, combined with a digital identity, can draw connections between individuals and their network of associates with great clarity. Where and how people choose to spend their money reveals much about their preferences. A subscription to a liberal-leaning magazine, a payment to a friend tagged as a troublemaker, the wrong ethnic profile: all these data could be used to identify and supress dissent. CBDCs are coinciding with a decline in the use of cash, and in authoritarian states it is easy to imagine a diktat that all transactions – certainly in cities and other technologically advanced areas where citizens would be expected to have access to digital technologies – must take place in CBDC, creating very little space to hide. Even an absence of activity may itself become to be considered suspicious as it has for Uyghurs who stop using their mobile phones.

Commercial banks used to pride themselves on being secret-keepers for their customers. Over the years, regulators have ensured they know who those customers are, and are monitoring for suspicious activity and reporting it to the authorities. However, the current system is still containerised with individual banks holding data about customers separately to each other, and no single state ID or ‘single file’ existing for each citizen. China’s banking and payments system has super apps at its heart like Ant Financial. It’s charismatic founder, Jack Ma, thought he was powerful and connected enough to level some relatively light criticism at China’s banking system. He was summoned to meet regulators, their IPO was cancelled wiping $76bn off the companies value and he disappeared from public view for three months. The private sector operates at the discretion of the party, and the leash is short. China have shown moves towards creating singular state records of citizens tying multiple data points together. Their moves towards CBDC, combined with their crackdown on their own tech sector shows how feasible it is that they could use these financial data to further oppress their citizens.

The programmable and centralised nature of CBDCs could be directly brought to bear to circumscribe citizen’s freedoms, both actively and through financial nudges. Posting the wrong thing on social media, joining a protect, or leaving a designated geographic area could feasibly result in an individual being frozen out of their money or placed on the monetary equivalent of emergency rations. Pro-regime behaviours and spending could be subsidised and rewarded using the programmable features of CBDC to incentivise spending with party-affiliated activities and loyalty. This may sound Orwellian or like a China scare story, and some of their early CBDC developments do make provisions for some level of privacy, but as both the morphing use of their covid apps and the wider treatment of their own citizens shows, it’s a frighteningly real possibility the once adoption becomes widespread it could be used as another tool of control.

Tied into this concern is how China has become a major exporter of oppressive technologies to other authoritarian or would-be authoritarian regimes. Several of these countries have shown early signs of wanting to create interoperability between their putative CBDCs. While this could come with the benefits of eased cross-border payments, it could also portend a more atomised global financial system, with less reliance on traditional western intermediaries such as Swift and the IMFs special drawing rights and a move towards an authoritarian money axis. Recent sanctions against Russia show both the strength and the limitations of the west’s ability to use financial architecture as a lever: a new infrastructure that bypasses the control or oversight of western states would make it much easier for authoritarian states to operate around sanctions and restrictions in their dealings with each other.

I sometimes think about the students and lecturers that I met in China – about their arguments in the debates I judged about the need for the state to reflect the wishes of its citizens in order to maintain its legitimacy, about their hopes for themselves and their country– and wonder how they are doing now. I hope for their sakes that my fears about how CBDCs could be appropriated as a tool of control are misplaced.

Leave a comment